High visa walls, hostile diplomatic exchanges and a jingoistic political climate have failed to halt peoples’ instinctive desire and determination to reach out across the militarised India-Pakistan border, reviving pilgrimage corridors, rekindling nostalgic tastes of remembered cultures and founding new links of a younger generation’s shared futures.

On 4 March this year, 102 Rotary Club members from Delhi, Chandigarh, Parwanoo and Shimla in India crossed the border to the Kartarpur Gurdwara Darbar Sahib in the Punjab province of Pakistan. They were joyfully welcomed by 112 fellow Rotarians who had driven down from Lahore and Islamabad.

The meeting at Kartarpur was the fourth in a series of such solidarity exchanges taking place since 2022. The Gurdwara is considered the second-most important shrine of the Sikh community and lies less than three kilometres from the border.

A historic treaty signed in November 2019 between the two nations allows visa-free access for Indian pilgrims to visit the shrine in Pakistan. After a long pause due to the pandemic, when the Kartarpur Corridor re-opened in November 2021, the first Rotary visit last year had only three travellers from India. “Many people from India backed out at the last minute from the Kartarpur visit in February 2022 due to the political climate,” said Anil Ghai, a Delhi-based businessman whose family migrated to India from Chakwal, Pakistan, at the time of Partition.

He now spearheads Indo-Pak peace initiatives from Rotary India, and initiated Rotary’s Twin Sister Club project, which ‘twins’ Rotary clubs on both sides of the border. Since 2022 there has been a steady growth in demand with the number of applicants swelling to 150 this year.

Further enthusiasm has been generated by the goal of establishing an Indus Peace Park near the Gurdwara Darbar Sahib. Rotarians from Lahore donated PKR 72,000 to the Gurdwara committee. Steadily, the Kartarpur visits have gathered enthusiastic momentum.

“Seeing hundreds of Indians and Pakistanis meeting with brotherhood and affection at Kartarpur was a phenomenal experience,” says Rotary’s Anil Ghai. “They all want peace and normal relationships. We are all the same, except maybe for the religion—we share the same language, culture, food, traditions.”

Earlier, Ghai had facilitated a visit by four Lahore members of the Rotary Inner Wheel, the women’s division of Rotary, for a conference in Anand, Gujarat, in November 2022.

Mission youth

Particularly striking is the energy and enthusiasm of youth on both sides of the border and in the South Asian diaspora space of initiating and innovating efforts to come together in friendship and solidarity. Indeed, it is youth activism that is filling the relative vacuum of the past decade of people-to-people exchanges. Powered by the internet and social media, these individuals and collectives have found creative ways to enable people-to-people connections even in troubled times—through a shared culture of music, dialogue, art, comedy and a discussion forum of ideas.

One of the more notable names in this regard is Ravi Nitesh, co-founder of Aaghaz-e-Dosti, a youth-led initiative that was founded over a decade ago. Seeking to involve schoolchildren in the Indo-Pak peace process, they launched an annual ‘peace calendar’ competition inviting entries from schools on both sides of the border. Children were asked to send in paintings on the topic of peace.

“We used to get around 60 to 70 entries in the first few years,” says Nitesh, a Delhi-based petroleum engineer who sponsors the printing costs from his personal funds or with the help of friends. “In the past few years, this number has gone up to 300 to 600 entries per year. The idea is growing.” Besides the peace calendar, they host greeting-card exchanges between students of both countries.

Aaghaz-e-Dosti also initiated the Aman Chaupal informal sessions in schools in India by visiting journalists, academics or other eminent personalities from Pakistan, and vice versa. “Not just kids but the teachers too were influenced,” says Nitesh. “They would ask candid questions, there would be laughter. It opened minds.” The school initiative paused with the pandemic.

Aaghaz-e-Dosti is continuing to mobilise youth in sustaining the peace and solidarity momentum through iconic peace vigils and peace marches. Eminent journalist and peace activist Kuldip Nayar was the moving spirit behind the annual August 14-15th midnight candlelight vigil of activists at Wagah Border, between Lahore and Amritsar, before his death in 2018. He had reportedly urged the youth to take forward the ritual mission practised since 1982.

Aaghaz-e-Dosti took on the mission and converted it into a peace march starting from Delhi to Wagah. Nayar flagged off the first such march beginning in Delhi. “It was his last public appearance. He passed away on 23 August 2018 after we returned to Delhi,” says Nitesh.

Since then, with the peace vigil at Wagah Border sustained by the Punjab-based group Hind Pak Dosti Manch, Aaghaz-e-Dosti took the peace march to the Ferozepur Border in 2022, and plans to keep doing so for the next five years.

“People in these border areas, who are not exposed to the vitriol on television and social media, want peace. Those who live in metro cities and are fed misinformation every day from various sources are more inclined to keep the hostility between countries going,” he says. “We can’t change the adults’ way of thinking. So, we focus on school kids with the hope that the next generation will strive for peace.”

Art for peace

The world of art recognises no borders and has been active in bringing together artists and curators from India, Pakistan and the wider region. One of the pioneers in this informal peace movement is Khoj, the Delhi-based autonomous non-profit contemporary arts organisation. Since 1997, their art residencies have helped create a network of emerging and established artists from across South Asia.

One of the beneficiaries of Khoj’s farsighted vision is Lahore-born artist Masooma Syed, who met her husband, Kerala-born sculptor Sumedh Rajendran, at a Khoj residency in 2003. While art brought them together, visas and politics kept them apart. Eventually, in the face of legal and social barriers, Syed gave up the quest to live with Rajendran in his Delhi home and the couple set up homes in Kathmandu and Colombo instead.

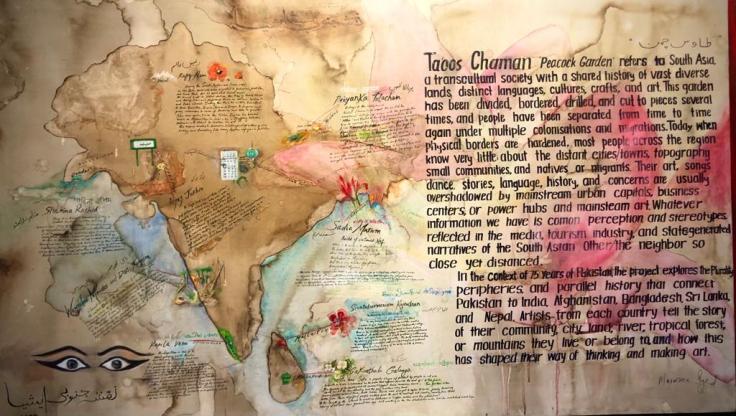

Syed, who teaches at art schools in Pakistan, Nepal and Sri Lanka, used her experience of living and working across South Asia to design a course on ‘Material Culture in South Asia’ for the cultural studies program at National College of Arts, Lahore. She also curated an ambitious show titled Ta’oos Chaman (‘peacock garden’) bringing together interdisciplinary artists and scholars from across South Asia to collaborate on areas of mutual interest.

Showcased online on Lahore Biennale Festival’s virtual museum, Syed’s show was created in collaboration with the British Council to mark Pakistan’s 75th anniversary, and was built around the theme of post-colonial identity and parallel histories in artistic practices in South Asia.

The title is borrowed from the Urdu short story Ta’oos Chaman ki Maina by late Indian scholar and writer Naiyer Masud. “The peacock garden here refers to South Asia,” says Syed, who finds the digital medium to be liberating for South Asian artists otherwise constrained by physical borders.

The show featured artists such as performer Kapila Venu from Kerala, India; Priyanka Tulachan from Pokhara, Nepal; Ayaz Jokhio from Sindh, Pakistan; Sadia Marium from Chittagong, Bangladesh; Sivasubramaniam Kajendran from Jaffna, Sri Lanka, and several others.

Syed gives credit to festivals such as the Lahore Biennale and the Faiz Festival for creating avenues for Indians to visit Pakistan and provide opportunities for cultural diplomacy. It is another matter that the recently held Faiz Festival 2023 grabbed news headlines across India and Pakistan for an irrelevant comment made by Indian lyricist Javed Akhtar rather than the many performances, talks and activities that underscored the shared artistic and cultural heritage of India and Pakistan.

Shared communitarian cultures

The clout of shared communitarian cultures has been effectively leveraged by Punjabis all over the world to transcend divisive nationalities. One such shared cultural space is Majha House, a cultural centre in Amritsar, India, for Punjabis from all over the world. Founded by publisher and activist Preeti Gill, the centre is established on her 40-year-old family property and serves as a platform for exhibitions, performances and talks. The events at Majha House are a combination of literature, film, music and poetry that celebrate the shared language and cultural roots of Punjabis across borders.

“Majha House is an effort to put Punjab centre-stage,” Gill said at eShe magazine’s Indo-Pak Peace Summit Led by Women 2021. “Partition is still like a living thing in Amritsar. They haven’t forgotten Partition, it’s still there, the stories are still there, the people are still there.”

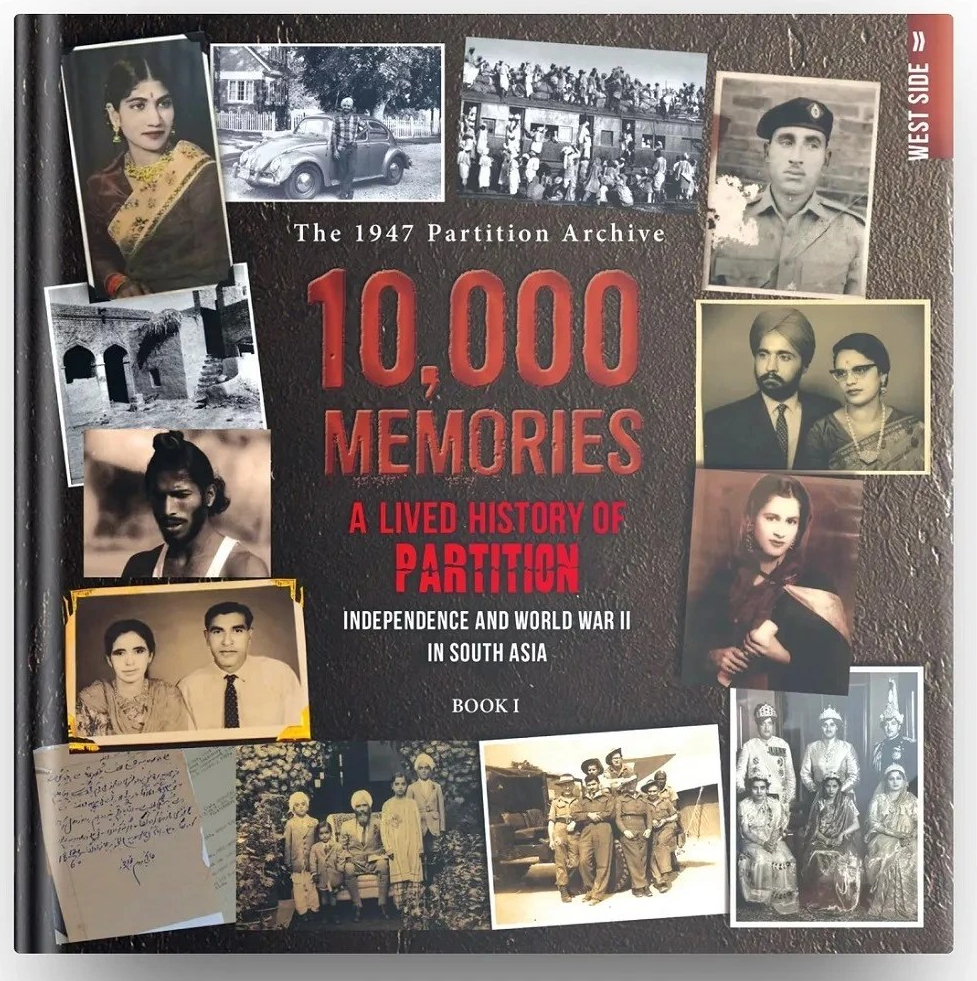

Partition is, in fact, the key point of shared history that has been the theme of several initiatives on both sides of the border. Ten years ago, physicist Guneeta Singh Bhalla founded the 1947 Partition Archive, a charitable trust in India run by volunteers dedicated to institutionalising the people’s history of Partition through documentation, storytelling and exhibitions.

The platform has chronicled over 10,000 oral histories of survivors and witnesses in hundreds of towns and villages, spread across 14 countries. These stories are chronicled in the book titled 10,000 Memories, which includes over a thousand photographs from both sides of the border.

A commitment to a people’s history also forms the basis of the work behind Project Dastaan, a unique youth-led peacebuilding initiative that uses technology to help partition refugees and immigrants from India and Pakistan revisit the land of their birth. The young team finds the exact locations and memories that these survivors seek to revisit and recreates them through bespoke 360-degree virtual-reality experiences.

They have also created an animated virtual-reality documentary A Child of Empire to help viewers experience a migrant’s state of mind, and a three-part film series The Lost Migration about lesser-known Partition narratives.

Pop culture

Films have of course always been a powerful way to bring Indians and Pakistanis together. From Bollywood films to Pakistani television serials, nothing unites the subcontinent more than a visual treat of drama, emotion, colour, music and dance.

Sometimes, there is a larger peace agenda behind these productions. Shailja Kejriwal, chief creative officer, special projects, Zee Entertainment, was the first Indian producer to commission films by Pakistani filmmakers for mainstream television in India. The shows were part of Zeal for Unity, Zee’s apolitical platform to promote Indo-Pak solidarity. Launched at Wagah border in 2017, the initiative initially brought together 12 celebrated directors including Mehreen Jabbar and Sabiha Sumar from Pakistan and Aparna Sen and Ketan Mehta from India. “The most common response from the Indian audiences was love. Everyone said, ‘Hum kitne similar hain’ (we are so similar),” said Kejriwal.

Another film-based initiative by the international non-profit Seeds of Hope titled Kitnay Duur Kitnay Paas brought together 42 young filmmakers from India and Pakistan supported by three mentors. Eight cross-border teams produced eight digital stories. Each film was shot on both sides and tied together with themes of shared culture, history and tradition.

Besides films, music is another great unifier and social media has inadvertently played a major role in bringing music lovers of the two nations together. Take the case of Coke Studio Pakistan. Even more popular in India than the Indian edition, the music show has taken Pakistani talent to millions in the subcontinent and created a cosy corner in YouTube for cross-border fan exchanges.

Its Season 14 megahit Pasoori by Ali Sethi and Shae Gill, garnered a staggering 600 million views on YouTube in a year of release, and was the unofficial anthem outside the Melbourne Cricket Ground after the India-Pakistan cricket match at the ICC T20 World Cup in October 2022. On their part, Pakistani YouTubers have helped popularise the television show Indian Idol in Pakistan, spotlighting their favourite performances and episodes.

The internet has opened several avenues for peaceniks to get together and for culture lovers to learn more about the richness and diversity of South Asia as a whole. Facebook groups such as India-Pakistan Heritage Club and Instagram accounts like Brown History curate news and stories from across the subcontinent, and create room for dialogue. People’s networks like Southasia Peace Action Network (SAPAN), of which this writer is a founder member, are creating safe spaces for discussion and activism across the region. Sapan has undertaken an online petition ‘Milne Do’ campaigning for easing of visa restrictions in the subcontinent.

In multiple fora, and in diverse forms, the people of India and Pakistan are reaching out and connecting with each other. As the Rotarian Ghai stated, “No matter what the governments say, the common people know that peace is beneficial for all of us.”

Leave a comment